Letters to the Post Office: “It is these discrepancies that are turning my hair gray.”

By Deborah Fisher and Kellen Diamanti

Editor’s note: The National Postal Museum is happy to host guest bloggers Deborah Fisher and Kellen Diamanti, who recently spent time in the National Postal Museum’s library collecting information for their forthcoming book about the famed Inverted Jenny, entitled Stamp of the Century.

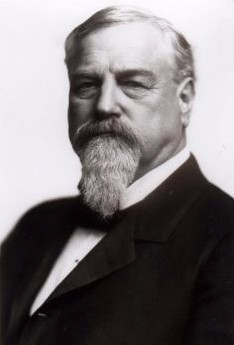

Third assistant Postmaster General Alexander Dockery was the first government official to cope with the flood of mail inspired by that problematic first airmail flight from the Potomac Park polo ground in Washington, D.C., on May 15, 1918, and the bi-color 24-cent “Jenny" stamp created for it. In the decades since, the flood may have slowed to a trickle, but letters to the post office and the official replies continue. A great deal of Post Office Department correspondence resides in the archives of the Smithsonian National Postal Museum, and it came to light during our research on the Inverted Jenny for our book, Stamp of The Century.

Perhaps one of the most overqualified individuals ever to step into the unheralded position of third assistant postmaster general, Dockery conscientiously embraced the job. His superiors, Postmaster General Albert Burleson and second assistant postmaster general Otto Praeger, may get the historical credit for launching airmail, but Dockery midwifed the stamp. He sent the airplane photos for the Bureau of Engraving and Printing to copy, received the die proofs for approval, and forwarded the postmaster general’s authorization to the Treasury Department. He even calculated the number of stamps likely to be needed, about one million per month, and issued postal bulletins announcing its creation.

Many letters were pure requests. Two weeks after the first flight, Senator John Shafroth of Colorado requested a pen-cancelled strip of stamps with the plate number attached for a constituent. Dockery politely declined because “the Department has none.” Two months later, Mr. K.B. Stiles seems to have hoped for invert copies of his own, to which Dockery explained that only one sheet had been found, though “it is understood some were discovered and destroyed in the Bureau of Engraving and Printing.”

Two years later, Dr. Paul Roth, Director of Clinical Laboratories for the Battle Creek Sanitarium, wrote the Treasury Department, urging the creation of a special stamp honoring airmail, which he was certain, “would be of considerable historical value.” He exhorted the department by concluding, “You will undoubtedly agree that if a step of this kind is taken it should be done without delay.” The letter was passed to the very patient Dockery who tactfully informed Dr. Roth that three issues of such a stamp had already been done, closing, “The interest in the postal service which prompted your letter is appreciated.”

As late as 1938, a worried reporter for the Boston Sunday Post successfully sought reassurance from the Post Office that no one had been disciplined for failing to intercept the sheet of errors.

A different sort of letter contained in the archives casts light on the pilot error that resulted in a nose-down, propeller-plant in a muddy field located in the opposite direction from that which he was supposed to fly out of Washington, D.C. The pilot, Lt. George Boyle, had received the plum assignment because he was the future son-in–law of someone important. Rather than sneer, a generous Reuben Fleet, the talented army major charged with creating the flight side of the airmail service simply commented in a reflective letter much later, “We should…not criticize Lt. Boyle too severely for his failures. He simply lacked enough training to do the job.”

Over the years, some official correspondents have been considerably less gracious than Alexander Dockery in their responses to questions from the public. Asked in 1941 what sort of plane was on the famous stamp, a Bureau of Engraving and Printing official wrote back, “BEP is unable to furnish the information.” Many Post Office Department administrators after Dockery were just as terse.

Still, withholding information is probably better than using official letterhead to create urban legends. In 1937, an official wrote an Illinois man who wanted to know the error sheet story, stating “that the first purchaser who was offered this sheet noticed the discrepancy and refused to accept the same. The next purchaser, however, sensing the philatelic value thereof, bought the sheet and later resold the stamps at a handsome price.” William Robey, that now-famous purchaser of the sheet of inverts, debunked that story himself the following year when his personal account was published in the Weekly Philatelic Gossip. Another rumor spread by the post office was that old chestnut claiming that forty-seven of the precious inverts had been lost when E.H.R. Green’s yacht sank in 1919.

“It is these discrepancies that are turning my hair grey,” wrote Gwladys Bowen, a reporter for The Oregonian on February 25, 1938, in one of three detailed letters to the Post Office Department. Having gathered every fact she could for an authoritative article on the Inverted Jenny, she sought clarification on a number of issues. “Authorities in the stamp collecting world are divided in their opinions as to whether the stamp was issued in sheets of 400, or in sheets of just 100 subjects each,” she wrote to the Office of the Third Assistant Postmaster General. This and her other questions about numbers, guide arrows, and margins prompted a meticulous reply from the Post Office, explaining how sheets of correct stamps then on display were printed and trimmed in way that showed two straight edges, ending with, “many collectors have inferred that the stamps were printed from 400 subject plates, which is not true.”

[On a side note unrelated to the Jenny, Gwladys Bowen had her own interesting history. Born in Connecticut in 1893, she was the daughter of a cavalry officer who had served under Nelson Miles, the man charged in 1876 with rounding up Lakota braves after the Battle of Little Big Horn. He’d witnessed Sitting Bull’s surrender and participated in the Nez Perce campaign that captured Chief Joseph, known for his tragic surrender, “I will fight no more, forever.” Gwladys attended the University of Oregon where her father was preparing students to fight in World War I. She went to work in Portland as a news reporter and lived to the age of 98.]

One of the best letters to the Post Office Department came from Stuart Borman of South High School in Valley Stream, Long Island, on Feb. 29, 1961, requesting information he needed for a book he planned to write. “I am looking forward to going to college. I am planning on writing a book about a near perfect crime having to do with the famed stamp find of William Robey. This book could very possibly be the key to my college career.”

Within a week, Director of the Division of Philately, Franklin Bruns, Jr., answered, “I am, of course, quite interested in knowing that you are planning a book about near-perfect crime involving the famed 24-cent air mail invert.” Bruns then referred the budding novelist to Inverted Jenny expert and editor of the Collectors Club Philatelist, Henry Goodkind, who lived near Stuart in New York.

We found Stuart, who did become a writer, albeit one specializing in chemistry, but he doesn’t remember that particular burst of youthful enthusiasm. However, he has been a collector of U.S. stamps since high school and also cares for his mother’s collection focused on the stamps of Germany. Just last year Stuart and his wife visited the National Postal Museum for the first time and saw a copy of the Inverted Jenny. Hearing that his letter has been saved along with the reply, he is eager to come back.

About the Authors

Kellen Diamanti and Deborah Fisher live and write in the Pacific Northwest. More about their book, scheduled for publication in spring of 2018, can be found at: stampofthecentury.com. Read about their research adventures in D.C. here: Treasure-Hunting Heaven.