The Union’s victory in the Civil War allowed for the emancipation of Southern slaves and provided African Americans with many rights which had been withheld under the institution of slavery. Under universal male suffrage, the “black vote” was essential to elections and as a result, several Republican presidents were voted into office.(1) To reward those who had helped in their election, successful Republican politicians appointed more than 1,400 African Americans to political offices in the South. Although 19th century postal records do not record the race of employees, close to 500 African Americans, including 116 postmasters, are known to have served during Reconstruction.(2) Their employment marked a break in postal segregation for almost 40 years.

Note: The data used in these graphs does not represent a complete record of all African American postmasters, letter carriers or clerks. Rather, the data represents the African American postal employees about which Jennifer Lynch, research analyst in the United States Postal Service, found information. Data came from the United States Census, Postal Service records, the National Archives and Records Administration, historical newspapers, previously published papers and records, among others.

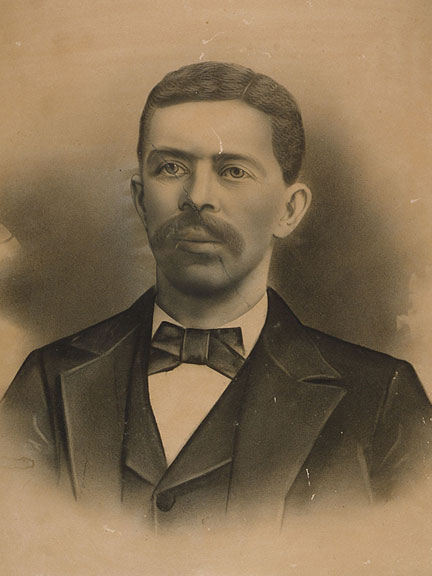

Many major cities including Charleston, South Carolina; Little Rock, Arkansas; and New Orleans, Louisiana and some small southern towns had African American postmasters during Reconstruction(3), many of whom were considered “eminently qualified for the office.”(4) The majority of these postmasters had been free before the Civil War. Some, however, were former slaves who had been educated either while serving in the Union army or in schools established by the Freedman’s Bureau.(5) The earliest known African American postmaster, James W. Mason was appointed in Sunny Side, Arkansas on February 22, 1867.(6) The highest paid African American postmasters, Charles W. Ringgold, and Dr. Benjamin A. Boseman, from New Orleans, Louisiana, and Charleston, South Carolina respectively, each earned $4,000 annually.(7)

Many 19th century African American postmasters, in addition to their postal department jobs, served important roles in the community. Pierre Landry is one such example. Landry served as postmaster in Donaldsonville, Louisiana from 1871 until 1875.(8) In addition to his postmastership, he became the first known African American mayor, elected in Donaldsonville in 1868.

In the late 1800’s many African Americans held the position of letter carrier. Approximately 150 African American letter carriers were appointed during Reconstruction and beyond. John W. Curry is one of the earliest known letter carriers. Curry began working as a clerk at the Washington, D.C. Post Office in 1867 and then joined the carrier force on April 20, 1870.(9) He served until about 1897. Additionally, all of the five letter carriers in Petersburg, Virginia were African Americans in 1879. There were also at least 15 African American letter carriers in Washington, D.C. during this time. Ten of these carriers were chosen to be honorary pallbearers at Frederick Douglass’ funeral in February 1895.

Throughout the second half of the 19th century, newspapers in both the North and the South ran articles announcing the appointment of African American postmasters, carriers, and clerks. The Atlanta Constitution published an article on May 10, 1891 headlined “Negro [sic] Postmaster.”(10) The article, like many articles of this time discussed the advancement of the African American in the Postal Service. The newspaper articles also address concerns from some white townspeople. These Reconstruction period newspaper articles illustrate the successes while also addressing the challenges African Americans faced during this time.

Despite the progress made by African Americans they still encountered many obstacles and a great deal of hostility from white citizens. One major obstacle newly appointed African American postmasters encountered was the feat of obtaining bonds.(11) Just like other political officials, postmasters needed to be bonded before taking office. Property ownership was a requirement for receiving a bond. This proved difficult for many African Americans who did not own property. This obstacle was expressed by John R. Lynch of Mississippi, a former slave who was elected and served as a United States Congressman from 1873 to 1877. He described the difficulties he experienced while trying to secure a bond following his appointment as a justice of the peace in 1869. “Then the bond questions loomed up, which was one of the greatest obstacles in my way, although the amount was only two thousand dollars. How to give that bond was the important problem I had to solve, for, of course, no one was eligible as a bondsman who did not own real estate. There were very few colored men who were thus eligible and it was out of the question at the time to expect any white property owner to sign the bond of a colored man. But there were two colored men willing to sign the bond for one thousand dollars each who were considered eligible by the authorities. These men were William McCary and David Singleton.”(12)

The end of Reconstruction in 1877 ushered in the return of white supremacy throughout the South. Nevertheless, Republicans continued to appoint African American postal employees. With increased racial prejudice, many African American postal employees experienced hostility and violence from white citizens. Several newspapers highlighted the strained race relations with such headlines as those found in the Cleveland Gazette and the Union, “Another Postmaster’s Home Burned”(13), “Bulldozing a Postmaster”(14), and “Postal Clerk Lynched.”(15) The article, “Bulldozing a Postmaster”, explains how Postmaster Thomas G. Robinson received anonymous letters warning him that if he “did not resign he would be killed.” After not complying with the threats, Robinson was awakened in the middle of the night as angry white citizens shot bullets through his bedroom window. These articles all tell of hardworking, diligent postmasters who, after refusing to step down from their positions in the post office, were threatened, bullied, and even murdered by angry white townspeople.

Even though many African American postal employees experienced hardships in their jobs, the Post Office Department continued to appoint African Americans to high level positions. John T. Jackson Sr., for example, served as postmaster at the Alanthus, Virginia Post Office for 49 years.(16) He served from 1891 until 1940, when he retired. Another postmaster, Joshua E. Wilson served Florence, South Carolina on four different occasions.(17) He began his appointment as postmaster in Florence in 1876 and retired in 1909. Additionally, the Post Office Department appointed two African Americans to high ranking positions in 1897. George B. Hamlet was appointed Chief Postal Inspector, and John P. Green was appointed Postage Stamp Agent.(18) Hamlet had worked for the Postal Department prior to the appointment. He had served as a postal inspector, and as Inspector-in-Chief of the Washington Division. As Chief Postal Inspector, he earned a salary of $3,000 a year. In his position as Postage Stamp Agent, John P. Green supervised eight white employees. According to an article in the August 3, 1897 issue of The Washington Post, Green’s position was “one of the most lucrative sinecures in the department.” The practice of appointing African Americans to postmasterships, especially in the South, came to an end during William H. Taft’s presidency (1909-1913). During his presidency, Taft segregated the Census Bureau, setting an example to be followed in other government agencies during Wilson’s Administration.(19)