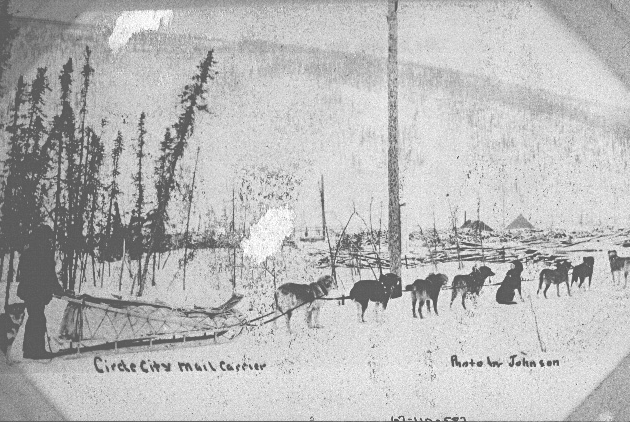

Photo courtesy of the University of Alaska, Fairbanks

When mail has to travel by dog sled, weight is critical. Carriers would bring first-class mail, but newspapers, magazines and packages were left behind. Sometimes correspondents slid newspaper clippings and gifts into letters, but if the package was too thick, suspicious carriers would leave it behind for the spring steamboats.

Winter mail was precious to the lonesome populations in the far north and they were quick to shower their wrath on carriers or postmasters who moved too slowly.

Photo courtesy of Special Collections Division, University of Washington Libraries, Cantwell 13

The struggle to get to the gold fields was too great for many of the green stampeders. After they lost their goods when their ship was swamped on the way to Dyea, Mr. and Mrs. Rowley went to work packing freight to raise enough money to keep going. When Mrs. Rowley received a letter from her brother which referenced $100.00 that he had sent (and which she had not received), it was enough to send her into a rage. She grabbed a pistol and set out to shoot the postmaster at Dyea, shouting that he had stolen her money. Although she did not shoot the postmaster, she was still arrested for attempted murder.

Stars of the Trail »

Photo courtesy of the University of Alaska, Fairbanks

At Valdez, Alaska, mail piled up for several months because it could not be taken further north. The local postmaster (only recently appointed by postal inspector John Clum) could not handle the pressure of the ever growing sacks of mail. He panicked and fled both the post office and the territory.

The flood of correspondence overwhelmed Canadians and Americans alike. Faced with similar circumstances—huge piles of mail and no way of sending them on—the postmaster at Gelnora, Canada tried to solve the problem by burning sacks of mail. He was rushed out of town with a mob hot on his heels.

Photo courtesy of the University of Alaska, Fairbanks

Alaska's mail carriers were courageous souls. They trekked over the winter trails when no one else dared to step outside to keep their schedules. When the weather was warm and the rivers ice-free, steamboats and canoes carried the mail. But, until airplanes were put into common use, dog sleds were used by most Alaskan carriers during the long, harsh winters.

January 24, 1902, from Dawson

"Many lives have been lost [on the unsafe ice]. Two mail carriers were drowned and mail lost. . . . I have sent out about 17 letters this winter had replies from none, that is the worst feature of the country. It is not right and I do not think necessary. American mail comes as far as White Horse I am told and many times it is left there until the boats come in."

Julia Musgrave, in a letter to her friend Ellen Hazard. From the collections of the University of Alaska, Anchorage.

Photo courtesy of the Yukon Archives, Gillis collection

Dog sleds loads were not to exceed 400 pounds, but the weight varied greatly. Postmasters and carriers usually held firm to their rules of no newspaper or magazine mail during the winter months. The enormous loads of first class mail was enough to tax the dogs' strength.

Of course, the Americans in Dawson, often desperately awaiting word from home, had little respect or regard for weight limitations. For most Americans in Dawson, griping about mail was second only to discussing possible new and exciting gold strikes.

One Mail Contractor's View »

Photo courtesy of Special Collections Division, University of Washington Libraries, Cantwell 42

Mary Hitchcock and Edith Van Dorn, two wealthy and adventurous women who were "doing the Klondike" as tourists in the summer of 1898, were surprised by the tediously slow gold rush mail service. In her book, "Two Women in the Klondike," Mary Hitchcock wrote about their introduction to Klondike mail service.

[Thursday, July 28th] "The first visit that Edith and I paid this morning was to the post-office, to inquire for the large batch of mail we supposed had been sent in to us over the Pass. To our great astonishment there was but one letter. We sent for the postmaster, who listened most courteously as we told him of the books, magazines, and papers which we had ordered to be forwarded long before our departure. He politely explained that a very small mail had been sent in over the Pass, but that the greater quantity would come by the Alliance according to contract made by our Government. First disappointment."

Hotel Ballard, Dyea

April 1st 1898"Dear Clara, I hurried your other letter off thinking it would go out that night, but I think it has not gone yet. Mail here is very uncertain. For instance, a letter from Skaguay to Dyea goes back to Juneau, a hundred miles, and then is returned to Dyea. Distance from Skaguay to Dyea-five miles. Much of the mail is "accommodation" that is brought in or out by the boats without pay. Uncle Sam has not yet found out that there are two lively towns up here. In another year he may have his attention drawn to the fact.

Mac"

Alfred G. McMichael's correspondence from the Chilkoot Pass trail. Letter from the collections of the Alaska State Library, Juneau.

Stampeders routinely chastised the inadequate mail service in their letters home. Even worse than no mail sleds or steamers was to wait in line for hours just to hear the words, "nothing for you."

Lake Bennett

May 8, 1898"My Dear Clara, At last I have been rewarded for my trip after mail. When I reach camp again this will have been a forty mile one but I have seven letters to show and a few supplies which I picked up. One each from Sara and Miss Kellogg and five from you so it is all right. I got up at three this morning (it was daylight) and started while the ice was good. In the morning I shall start by four for my twenty mile walk. Think of me doing forty miles on foot when a two and a half mile trip downtown on foot was quite a consideration.

I have not paid $1.75 with as much pleasure since leaving home. I hope more will come for I think I shall be able to get them in a couple or three weeks again.

I will write soon again and get it started out, and I think now the Canadian government has established offices at two or three places below here where we can mail letters.

Now I must say good night for it is late. Love to all and more kisses for the children.

Yours, Mac"

Alfred G. McMichael's correspondence from the Chilkoot Pass trail. Letter from the collections of the Alaska State Library, Juneau.

Photo courtesy of the Anchorage Museum of History and Art

Gold strikes continued to be made across Alaska over the next several years. Each new strike brought hundreds to thousands of miners into the area. And each time the miners found themselves lined up once again in hours-long lines at new post offices.