The Postmaster General Collection

By Annette Shumway, Museum Technician

As a graduate student in Intro to Museums class, it floored me to learn just how many wonderful objects were present in museum collections but were not being exhibited. This prompted me to research and gain experience in digitization of collections. Now as an employee assigned to the Postmaster General Collection, I am thrilled to think of the digitization possibilities for this collection.

What exactly is the Postmaster General Collection?

The Postmaster General Collection (PMG) consists of two distinct collections: the philatelic collection, which contains postage stamps, die proofs, essays and other material related to the printing of stamps and postal stationary; and the art collection, which contains the original artwork that the Postal Service has commissioned for U.S. stamps for the last 75 years. The philatelic collection was started in the 1860s by the Post Office Department (POD). Under the POD and its successor organization the United States Postal Service (USPS), it has grown to include postal stationary, uncut press sheets, and metal printing dies and drums.

Under an agreement with the USPS, the PMG collection has been deposited on long term loan to the National Postal Museum (NPM). In exchange for the collection, the museum staff is responsible for the care and management of the collection and for making it available to the public. As part of the cataloging process, we will identify and describe each object, being sure to include information such as its dimensions and material types-- and safely store it in containers that will extend its life.

Cataloging the philatelic (stamp and other postal matter) portion of the collection began in summer of 2010. At that time, we were re-housing and cataloging the objects prior to moving them to NPM storage. By the end of 2011, we had over 12,000 objects in the database. According to Smithsonian digitization standards, we could say these objects were digitized to an acceptable standard! Certainly, curators and researchers would now be able to quickly search through these records, sorting on various criteria.

In the fall of 2011, USPS also granted us the loan for the original artwork of many U.S. stamp designs - on the condition that we move it within three months. Wow! Considering that the artwork doubled the amount of objects we would be transferring AND we had not yet finished cataloging the philatelic portion, this was a pretty tall order. But we were up for the challenge.

I, along with my interns, Alexandra Nichols (pictured here, on the left, me on the right, unpacking a framed object) and Janelle Batkin (below, sealing the boxes before the move), worked diligently to sort objects and inventory boxes, unloading boxes that were overly stuffed, and adding cushioning to those that were not completely filled in order to stabilize the contents. And we measured! We measured everything from the boxes that needed custom lids to the opening in the doorway (needed to make sure those moving boxes fit once they were packed...) to the height of the loading docks of the various locations where the collection would be deposited.

Once at the museum, we opened the moving boxes, carefully checking the contents against our inventory list. Almost immediately there were Curatorial requests for objects from the collection. Having this list was essential to locating the objects within our 30 plus 2’x2’x2’ boxes. We worked through the spring to finish transferring the remaining philatelic objects into their containers. Shortly thereafter the cataloging of these objects resumed.

Next, we turned our attention to the art portion of the collection. Many of the original art objects had been grouped by Scott number (a number that designates the design and printing elements of the stamp or postal stationary). Because the art was wrapped in bundles of tissue paper and stored inside acid-free cardboard boxes, for the most part it is in good condition. However, some of the bundles were overcrowded and needed to be rehoused. The bundles also did not allow for ready access to the collection. We also saw instances where the bundles had been opened and the contents had been dispersed making it difficult to gather the pertinent objects quickly.

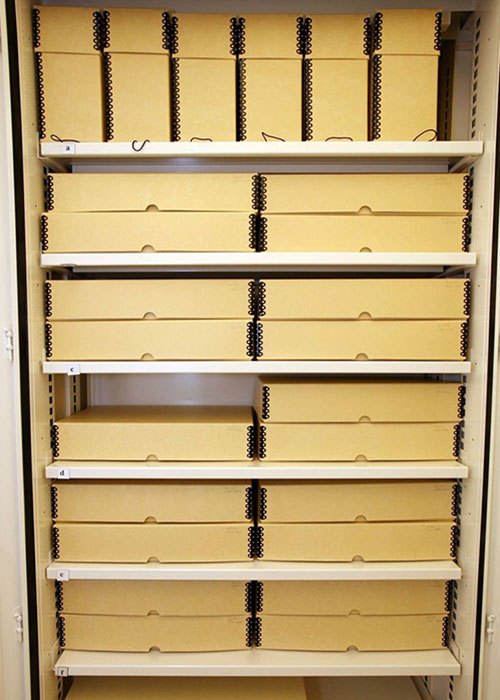

To answer these challenges, we placed the 2-D objects in acid-free folders and boxes, maintaining the Scott number order, but dividing them by size-small, medium, large and extra-large categories. Incredibly, much of the art is smaller than a newspaper page and thus fits into our small or medium categories. Once these objects are recorded in our database, it will take a few clicks of a mouse to gather the object locations, and from there a short while to physically reunite the objects in their original grouping, if the need should arise.

Looking to the future, our next phase is to ensure that the breadth and depth of this collection is captured in our database, imaged, and choice objects are loaded into our online collections website. If you live in the DC Metro area, some of the elements of the collection will be on display in the William H. Gross Gallery that is set to open in fall 2013. But for the rest of us, other portions of this long hidden gem may be coming to a computer near you.