The Most Interesting Mailboxes the Post Office Never Used

By Nancy Pope, Historian and Curator

In 1858 Albert Potts patented the first mailbox that the Post Office Department ever used. These new boxes, technically known now as collection boxes were then referred to as letter boxes, were placed on city sidewalks, giving people a chance to mail a letter without having to go to their local post office.

The Post Office Department began using new and better designs for its collection boxes and by the late 19th and early 20th centuries new collection box patents were being filed at an astonishing rate. The process started slowly with fewer than a dozen patents filed for collection boxes from 1860-1880. But that soon changed. By 1890 and 1909 over 100 patents were granted for collection box designs. Most were slight adaptations on existing designs, but some offered a variety of new services, improvements on the mere use of the boxes to collect mail.

In April 1889, Jonathan Morris of Hyde Park, Illinois, received a patent for a collection boxes for use in public buildings and offices. Among its unique features was a small receptacle for visitors’ cards, to hold cards containing information for the carriers, such as “not at home” or “will return.” The box is also divided into slots for “letters” and “papers” (periodicals and newspapers). This rather complex contraption was never selected by the Post Office for use on city streets.

In 1890, Paul Richter of New York City filed a patent for a box that was unlike any of the U.S. collection boxes of the time, but bore a striking resemblance to British collection boxes. These boxes would hold a pair of mailbags inside so that all a carrier had to do was pull out the mailbag, replace it with an empty one, and go on his way. Of course that didn’t take into account the fact that carriers collected mail from several boxes. So instead of having only one bag (that would become increasingly full), the carrier would have several bags to drag along with him on his route.

1890 also brought Eben Boynton’s clock-tower collection box. Boynton, of West Newbury, Massachusetts, offered this design as he believed “street letter-boxes of the present style are not only offensive to the eye, but are quite unsuited to postal requirements, inasmuch as they are suitable only for the reception of letters and postal-cards.” Mail could be inserted in the back of the clock on top of the tower, and gather inside the pedestal until removed by a carrier. Newspapers and periodicals could be inserted into the contraption at slot “d” in the design. While an interesting take on a collection box, Boynton’s clock-tower did not see day as a U.S. collection box.

Seven years later, Oswald Leuschner of Brooklyn tried his hand at improving the collection boxes when he received a patent for his “Improved Guide-Post” that would be “placed at street-crossings and to display various useful information, besides containing public calls and a letter-box.” The wildly ornate guide post included an eagle on top. Leuschner proposed columns that could contain direct lines to police precincts and hospitals, in addition to serving as a fire alarm box and letter box.

Byron Hargove of Bottom, Texas, proposed a collection box design in 1896 that would allow people to mark their mail with the date, thus perhaps freeing the Post Office from needing to add that information in their canceling devices? Although I’m not sure if the carriers gathering up mail from these collection boxes would have been enthused about making sure the date was right on each box and refreshing inking pads before moving on.

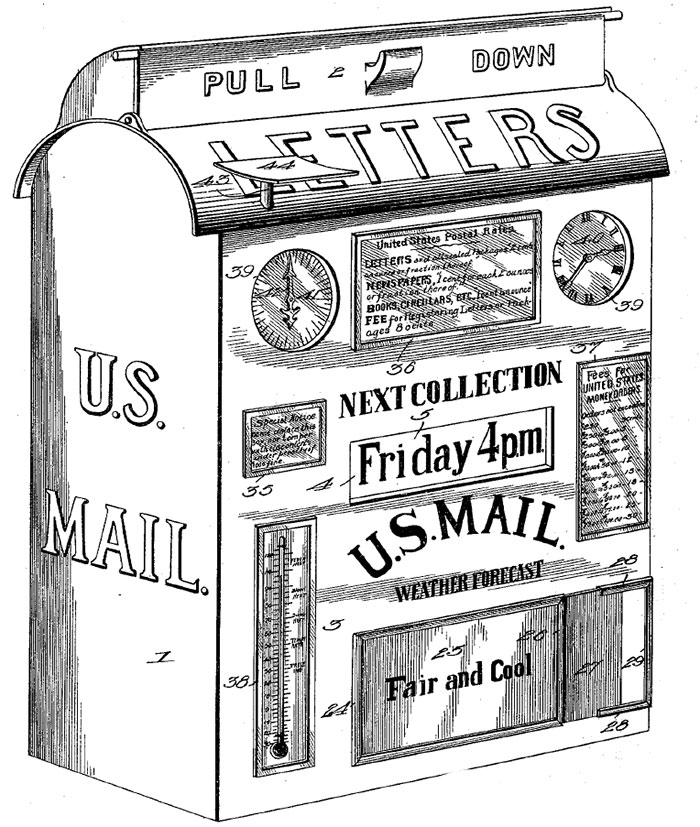

At the turn of the last century, inventers really went to town with collection box ideas. Warner Vestal of San Bernadino filed a patent for a box that offered mailing patrons much more than just a place to post their letters. The box would be used for clocks that showed the last and next mail pick-ups, notifications from the post office on everything from money order rates to mailing fees for newspapers, letters and books, and even a place for the day’s weather forecast and a thermometer for temperature readings! Vestal’s multi-tasking collection box never made it into production.

Finally, my personal favorite of all the collection box patents is George Alfred Owen’s decorative, multi-use and information design from his 1906 patent. Owen, from Springfield, Massachusetts, created a box that he said would not only provide for collecting mail matter, but also provide “an efficient automatic dating and stamp-canceling mechanism therein.” As Owen’s design shows, the box would clearly be marked with the terms “Automatic Register and Carriers Detector.” The box would have “an electric signaling device whereby on the opening of the letter-box access to an electric annunciator connecting with the post-office permits the carrier to report the exact time of his visits to the said box.” An addition that would, no doubt, have caused moans and groans from the carrier community. Owen’s box had two clearly marked receptacles, one for letters and one for bulk mail, each having its own separate collection area.

About the Author

The late Nancy A. Pope, a Smithsonian Institution curator and founding historian of the National Postal Museum, worked with the items in this collection since joining the Smithsonian Institution in 1984. In 1993 she curated the opening exhibitions for the National Postal Museum. Since then, she curated several additional exhibitions. Nancy led the project team that built the National Postal Museum's first website in 2002. She also created the museum's earliest social media presence in 2007.