Anthony Comstock was born in New Canaan, Connecticut, in 1844. He had a strict Puritan upbringing that would influence his later life. After having served in the Civil War, Comstock moved to New York City, which was seeing a rapid expansion in businesses of all types, including saloons and gambling halls. Comstock joined the city’s “Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA), which had issued a report in 1866 fearing that young men would fall into these “traps of immorality.” The report also cited the dangers of obscene books, calling them “the feeder of brothels.”(1)

Comstock began his crusade against vice slowly, but found support and assistance. In 1872 he worked with the YMCA to create the Committee for the Suppression of Vice. In 22 months the Committee arranged for thousands of books, photographs and printing plates to be seized in anti-vice raids. Financial supporters of the Committee came from among the city’s richest and most powerful families and, before long, his support spread to the nation’s capital.

Comstock’s supporters backed his efforts to convince Congress to institute a new federal anti-obscenity law. Legal experts stepped in to help refine the bill. Speaker of the House James Blaine agreed to push the bill through, it passed in 1873, and President Grant signed it on March 3. The bill, which became known for its champion, was nicknamed the “Comstock Act.” The first federal law to deal with obscenity in the mail had been passed in 1865. Comstock’s law strengthened punishments and widened definitions of obscenity (adding information about abortion or contraception to the list of indecent matter). Shortly after the bill was signed, Comstock received a commission as a Special Agent of the U.S. Post Office, giving him the power to enforce his law.

Comstock’s zealous pursuit of the printers and publishers of obscene material overwhelmed the other aspects of the law that he created and enforced. While arresting those who published materials that still would be considered obscene today, he also hunted and arrested those associated with legitimately artistic works. His enthusiasm for arrests and the breadth of his pursuits led to the creation of the word “Comstockery,” an overzealous moral censorship of art and literature.(2)

Chasing down purveyors of immorality was neither Comstock’s goal, nor the only ills his Act sought to remedy. The Comstock Act was concerned with a wide range of misuse of the U.S. mails. Comstock used his position to track down a variety of get-rich-quick promoters who used the mail during schemes to bilk Americans by selling counterfeit currency, and fake securities, land or mineral rights, among other endeavors. He also began looking into medical quackery advertisements selling “cures” for a wide range of ills.

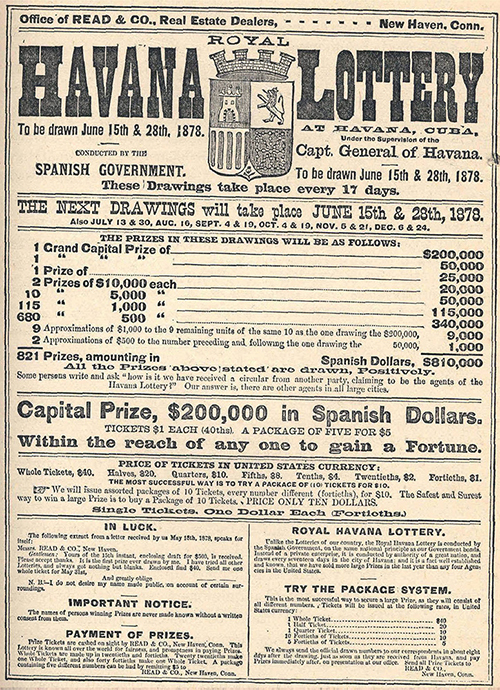

The illegality of foreign and domestic lotteries was also part of the new Act and Comstock was an energetic opponent of both. In 1872 the Louisiana Lottery Company was the only legal U.S. lottery in operation. In order to reach the widest number of people, lotteries often operated through the U.S. mail. The new Act forbade all lotteries and the Louisiana Lottery Company was to be put out of business. A side effect of that lottery shutting down was a huge drop in New Orleans’ mail volume. The city’s postmaster had to let nine clerks go when there was no longer work for them to do.(3)

Comstock continued his crusade and remained a special agent for the Post Office Department until his death in 1915. Bits and pieces of his Act were challenged and eliminated over the years. Birth control advocate Margaret Sanger was an influential force in successfully challenging some of that legislation. The last piece of Comstock’s Act came down in 1965 when the Supreme Court decision on “Criswold v. Connecticut” lifted all restrictions on the use of contraceptives by married couples.

- Young Men’s Christian Association of the City of New York, A Memorandum Respecting New-York as a Field for Moral and Christian Effort Among Young Men; Its Present Neglected Condition; and the Fitness of the New-York Young Men’s Christian Association as a Principal Agency for Its Due Cultivation, (New York: The Association, 1866) p. 6.

- Author George Bernard Shaw claimed he originated the term “Comstockery” in 1905 after Comstock worked to remove Shaw’s play Man and Superman from the New York Public Library. But the term dates to at least the 1890s in editorials. The term appears in 1897 in the Los Angeles Herald, and in 1895 in the New York Times.

- Another area of the Post Office Department was burgeoning. Comstock’s enthusiastic crusade brought a need for more assistance in finding and arresting violators of the Act. Through the 1870s, the Post Office Department’s number of special agents (a.k.a. postal inspectors) grew from just 20 in the 1860s to 100 by 1897.