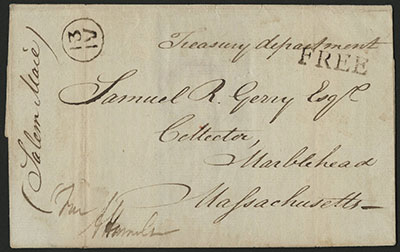

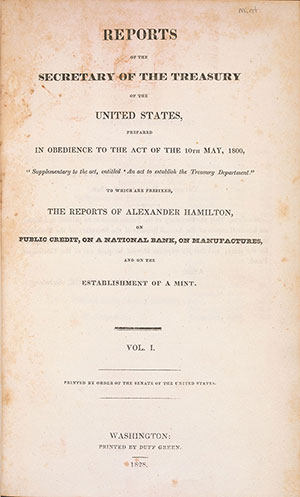

After Washington was elected president, he chose Hamilton to be his secretary of the treasury. Hamilton’s influence with Washington and the fact that he controlled the two largest government agencies made him a convenient lightning rod for critics of the administration who dared not directly assault the immensely popular president.

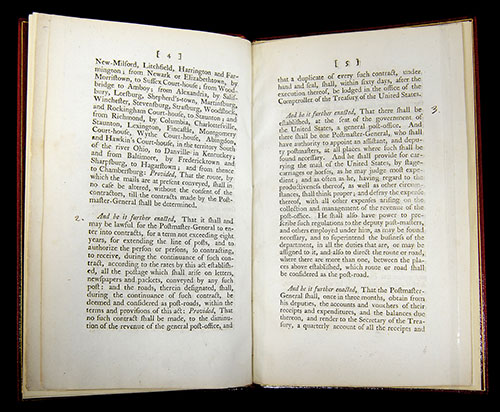

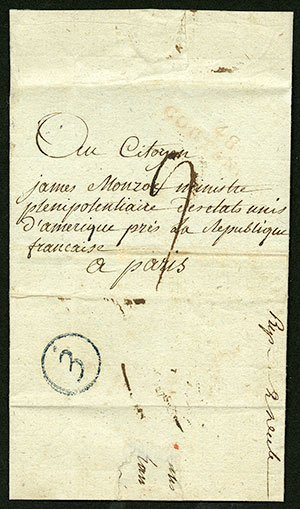

The major issues of Hamilton’s time at Treasury were paying Revolutionary War debts, maintaining neutrality in European wars, and defining the powers of the executive branch of government. In all of these, Hamilton played a pivotal role. By the end of Washington’s first term, national political parties were coalescing around support for and opposition to Hamilton’s policies.